Theory

Introduction

The Instruction Fetch and Execute Cycle is the process through which a central processing unit (CPU) performs the tasks necessary to execute instructions from a program. This cycle is the fundamental building block of any microprocessor or microcontroller and involves a series of well-defined steps that ensure proper execution of instructions stored in memory. In this experiment, the fetch and execute cycle is simulated using basic digital components such as flip-flops, logic gates, and clock signals.

Components Involved:

• Program Counter (PC):

The Program Counter (PC) is a crucial register in the CPU that holds the memory address of the next instruction to be fetched for execution. It ensures the sequential flow of instructions by incrementing automatically after each instruction fetch. After the current instruction is fetched from memory, the PC is updated to point to the address of the next instruction. In the instruction fetch and execute cycle, the PC coordinates the fetching of instructions from ROM (or RAM) and plays a vital role in ensuring that the program runs in the correct sequence.

•ROM (Read-Only Memory): ROM (Read-Only Memory) is a non-volatile memory where program instructions and fixed data are stored. In the fetch-execute cycle, ROM contains the machine code instructions that the CPU needs to execute. The Program Counter (PC) points to the address in ROM where the next instruction is stored. ROM is read-only, meaning that the data within it cannot be modified during regular program execution, which makes it ideal for storing the operating system, firmware, or boot programs that are essential for starting up the system.

• Registers:

Registers are small, fast storage units within the CPU used to hold data, instructions, and addresses temporarily during the fetch-execute cycle. They provide fast access to data that is needed immediately for processing. For instance, the Instruction Register (IR) holds the current instruction fetched from memory, while other general-purpose registers temporarily store operands or results during arithmetic and logical operations. Registers are vital for managing and manipulating data efficiently in the CPU, ensuring smooth execution of instructions and preventing delays caused by slower memory access.

•ALU (Arithmetic Logic Unit): The ALU (Arithmetic Logic Unit) is the component of the CPU responsible for performing all arithmetic and logical operations. It executes operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, AND, OR, etc., based on the decoded instruction. When an instruction requires mathematical or logical computation, the control unit directs the relevant operands to the ALU, which processes the data and sends the result back to a register. The ALU is a critical part of the CPU's execution cycle, enabling the system to perform calculations and make logical decisions.

Phases of the Fetch and Execute Cycle

•Instruction Fetch (IF): The first phase involves retrieving the instruction

from memory. This is accomplished using the Program Counter (PC), a special

register that holds the address of the next instruction to be executed. The PC

sends the memory address to the memory unit, which retrieves the instruction and

places it in the Instruction Register (IR). After fetching the instruction,

the PC is incremented to point to the next instruction in the sequence.

•Instruction Decode (ID): In this phase, the instruction stored

in the IR is decoded to determine its operation code (opcode) and any associated

operands (data or memory addresses). The control unit generates the necessary control

signals based on the opcode. These signals direct the data flow and initiate the

appropriate operations.

•Instruction Execute (EX): The execution phase uses the

Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) for computations and activates the required memory

or I/O components for data transfer.

Figure-1: Phases of the Fetch and Execute Cycle

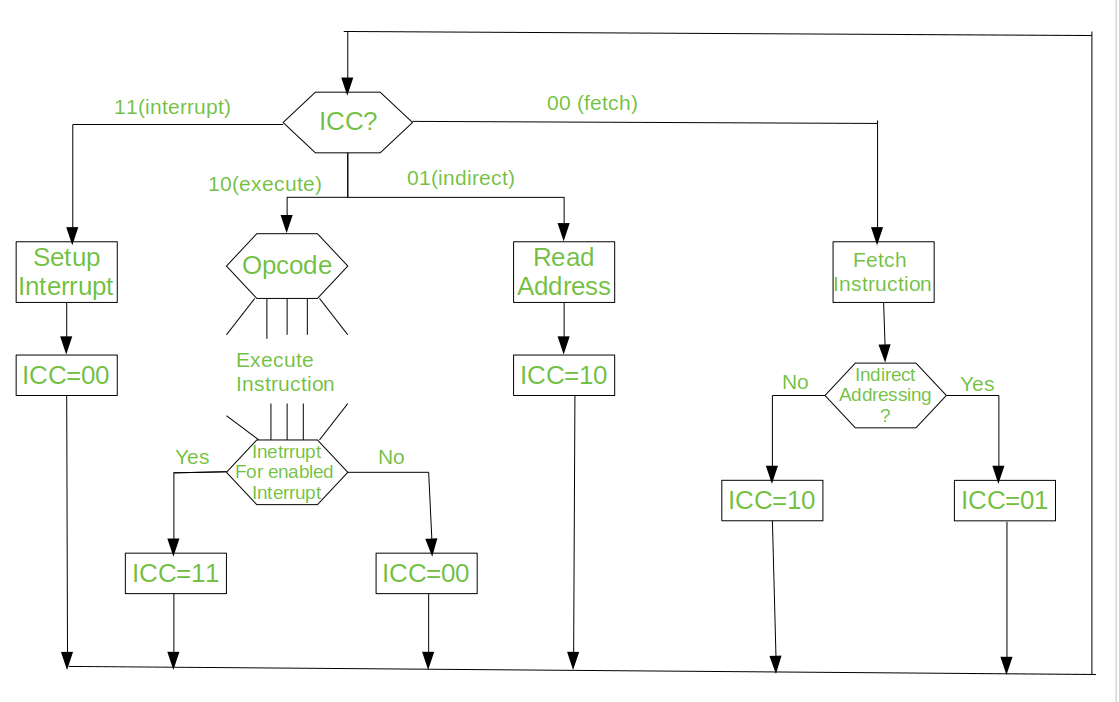

Different Instruction Cycles

• Fetch Cycle: The fetch cycle is the initial stage of the

instruction cycle. It involves retrieving the next instruction from memory.

The CPU uses the program counter (PC) to access the memory location where

the next instruction is stored. The instruction is fetched and placed in the

instruction register (IR).

This cycle ensures that the CPU has the next instruction ready for decoding and execution.

• Indirect Cycle: The indirect cycle is sometimes required

when instructions involve accessing memory locations that contain addresses

or pointers to the actual data.During this cycle, the CPU may use an address

obtained from the previous instruction to access another memory location,

which holds the data or another address to be used in the next cycle.

The indirect cycle enables the CPU to follow memory references and retrieve

the actual data required for execution.

• Execute Cycle: The execute cycle is where the central

processing unit performs the operation specified by the decoded instruction.

The CPU carries out arithmetic computations, logical operations, data

transfers, or any other actions as dictated by the instruction. This may

involve accessing data from registers or memory, performing calculations,

and updating registers or memory locations.The execution stage accomplishes

the intended operation and is where the actual work of the instruction takes

place.

• Interrupt Cycle: The interrupt cycle comes into play when an

external event or condition triggers an interrupt, causing the CPU to temporarily

suspend its current execution to handle the interrupt request.The CPU saves

its current state (program counter and other relevant information) before

jumping to an interrupt service routine (ISR). After servicing the interrupt,

the CPU may restore its state and continue execution.Interrupt cycles enable

a CPU to respond to external events or asynchronous inputs promptly without

losing important data or program context.

Figure-2: Flowchart of instruction cycle

Advantages of instruction cycle:

• Standardization: The instruction cycle provides a standard

way for CPUs to execute instructions, which allows software developers to

write programs that can run on multiple CPU architectures. This

standardization also makes it easier for hardware designers to build CPUs

that can execute a wide range of instructions.

• Efficiency: By breaking down the instruction execution

into multiple steps, the CPU can execute instructions more efficiently. For

example, while the CPU is performing the execute cycle for one instruction,

it can simultaneously fetch the next instruction.

• Pipelining: The instruction cycle can be pipelined,

which means that multiple instructions can be in different stages of

execution at the same time. This improves the overall performance of the

CPU, as it can process multiple instructions simultaneously.

Disadvantages of instruction cycle:

• Overhead: The instruction cycle adds overhead to the

execution of instructions, as each instruction must go through multiple

stages before it can be executed. This overhead can reduce the overall

performance of the CPU.

• Complexity: The instruction cycle can be complex to

implement, especially if the CPU architecture and instruction set are complex.

This complexity can make it difficult to design, implement, and debug the CPU.

• Limited parallelism: While pipelining can improve the

performance of the CPU, it also has limitations. For example, some

instructions may depend on the results of previous instructions, which

limits the amount of parallelism that can be achieved. This can reduce the

effectiveness of pipelining and limit the overall performance of the CPU.

Conclusion:

This simulation demonstrates the fundamental workings of a processor by implementing the fetch and execute cycle using flip-flops and logic gates. It provides a hands-on understanding of how control signals and data paths interact to execute instructions. This experiment is crucial for understanding the design and functionality of modern CPUs and their sequential operations.